Film Review: ‘Ex Machina’

Alex Garland's brittle, beautiful directorial debut is a digital-age 'Frankenstein' refashioned as a battle of the sexes.

While multiplex fantasy remains an extravagantly caped boys’ club, a stealthy gender inquiry is taking place in more specialized sci-fi territory, with Alex Garland’s brittle, beautiful “Ex Machina” its latest slyly thoughtful line of questioning. A worthy companion piece to “Under the Skin” and “Her” in its examination of what constitutes human and feminine identity — and whether those two concepts need always overlap — Garland’s long-anticipated directorial debut synthesizes a dizzy range of the writer’s philosophical preoccupations into a sleek, spare chamber piece: Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” redreamed as a 21st-century battle of the sexes. Exquisitely designed and electrically performed by Alicia Vikander, Domhnall Gleeson and particularly Oscar Isaac, this uncomplicated but subtly challenging film requires strong word of mouth from its January U.K. release (and its March SXSW premiere) if audiences abroad are to tap its porcelain surface.

“I’m hot on high-level abstraction,” brags 24-year-old Internet coder Caleb (Gleeson) early on in the proceedings — a qualification as necessary for the position of protagonist in an Alex Garland narrative as it is for the mysterious mission he’s assigned in the film’s opaque opening reel. Much of Garland’s fiction and screenwriting work is built on austerely abstract hypotheses, yet peopled by comparatively fragile characters unequal to the challenges of their story world. In its dramatization of a literal love affair between human and artificial intelligence — the same unsolvable conundrum that haunted the recent “Her” — “Ex Machina” follows suit, its updated mad-scientist study showing man’s capacity for invention exceeding his reserves of empathy. (In this case, at least, the gender-biased pronoun feels appropriate.) One might call it a cautionary tale, though Garland isn’t necessarily on humanity’s side.

Indeed, the film’s very first frame serves to distance viewers from their own: D.p. Rob Hardy’s camera peers at Caleb in his office as if from the reverse side of his computer screen, while muted audio suggests we’re observing him from a quarantined realm. As it turns out, he’s soon to join us there. It emerges that Caleb has won a competition staged by his employers, the world’s largest Internet provider, to spend a week with enigmatic CEO Nathan (Isaac) at the latter’s expensively hermetic woodland lair — dazzlingly envisioned by production designer Mark Digby as a palatial blend of Philip Johnson severity and Scandinavian laboratory chic.

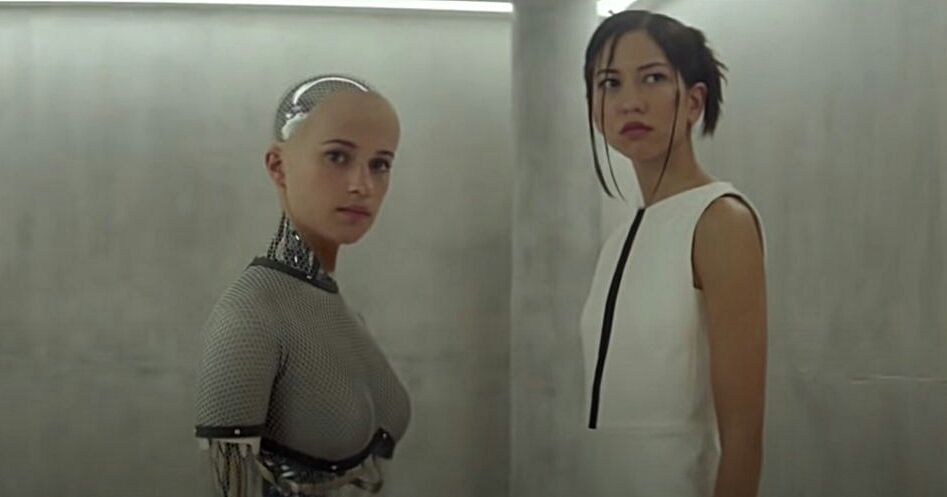

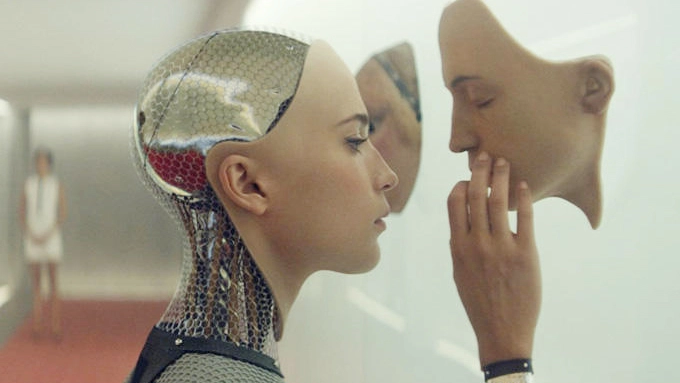

Upon arrival, however, the wet-behind-the-ears nerd discovers that his golden ticket is no luxury perk: Rather, he’s been recruited to participate in a cloistered research experiment, testing the limits and limitations of Nathan’s stunningly advanced new developments in AI technology. The boss’ most recent breakthrough takes the form of Ava (Vikander), a female-gendered robot whose expressive, peach-soft facial features belie her transparent synthetic form and complex exposed wiring. And so, during the first of Caleb’s seven planned consultation sessions with her, do her casual conversational ability and dry, even flirtatious sense of humor; somewhat surprisingly, Nathan has designed an organism as delicate and genial as he is brusque and self-absorbed.

Caleb’s task is to perform a Turing test on Ava, determining whether her thinking and behavior is, at any level, distinguishable from that of a human being — and if so, where the disconnect lies. (That, of course, makes “Ex Machina” the second film of recent months, following the much-garlanded “The Imitation Game,” to concern itself with the research of computer scientist Alan Turing. Furthermore, it arguably does a better job of honoring his intellectual legacy.) As the interloper falls hard and fast for the android, the test would appear to be passed with flying colors. But is she the only case study? And has her precise degree of consciousness and calculative ability been programmed by her creator, or has his expertise in this department exceeded his control?

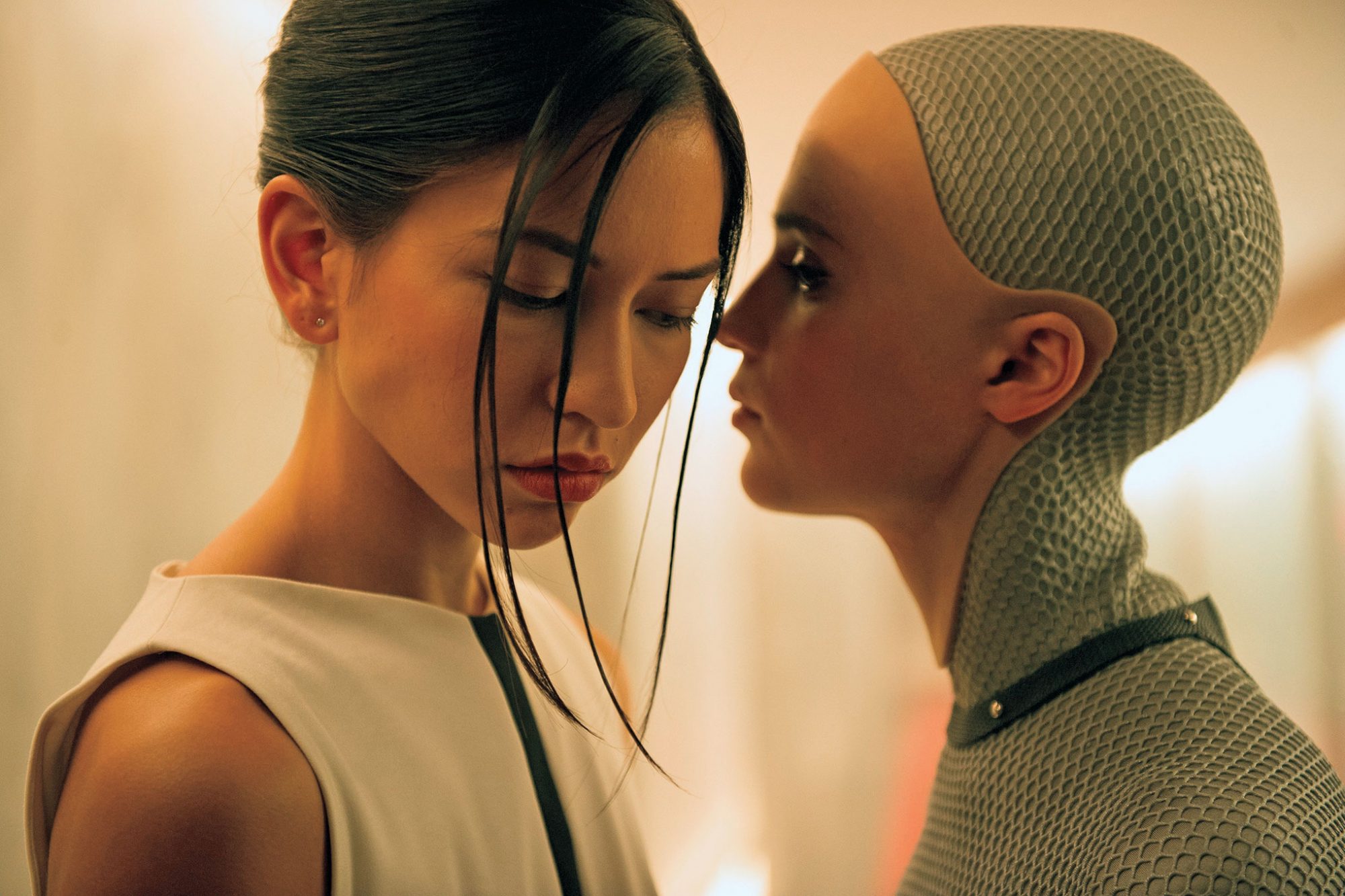

As the balance of power wavers between human and humanoid intelligence, a second dividing factor appears in this uneasy, quasi-incestuous love triangle, as Ava exhibits hints of a feminine intuition that the jockish Nathan seems unlikely to have formatted himself — even if, in a provocative detail that opens up further consideration of sexual hierarchy, he made sure to grant her functioning facsimiles of genitalia. “Ex Machina” turns out to be far wittier and more sensual than its coolly unblemished exterior implies; it’s a trick that mirrors Ava’s own apparent Turing-test-defying evolution. As further intricate psychological possibilities unfurl, the pic extends questions of mortality and human construction raised by Garland in his deft 2010 adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s genetic sci-fi parable “Never Let Me Go” — principally that of what humanity is worth if it can be so soulfully replicated.

Isaac has been in such a rare run of form recently that one fears for his ability to surprise, but it’s still intact here. Cutting a more baleful figure than usual with his dense beard and scalp-skimming buzz cut, his Nathan responds to the world around him — the limited world he’s curated for himself, at least — with unfazed-sounding comebacks and laid-back swagger that ultimately betray the strenuous effort behind them. It’s the piercingly funny sendup that the “tech-bro” elite has had coming for too long, but Isaac is too nuanced a performer to leave it there, never neglecting the petulant brilliance that finally makes this designer Dr. Frankenstein a tragic figure.

Garland’s script doesn’t grant Gleeson and Vikander quite the same liberty to play, but both actors turn in remarkably disciplined work, articulating a burgeoning romance in which the boundary between real and simulated feeling is kept teasingly ambiguous throughout. Swedish export Vikander, whose shimmering physical presence increasingly recalls that of her compatriot Ingrid Bergman, aces a particularly tough assignment in Ava, a cipher whose every gesture and vocal inflection renders her at once more human and less explicably alien.

Filmed on an approximate budget of just $15 million, the film looks and sounds immaculate at every turn, with its contained, interior-based three-hander structure permitting the money to be lavished less on locations and more on eerily vivid digital and prosthetic effects. (The film’s sporadic attempts to “open out” proceedings, as when a dialogue-driven scenes is situated by a waterfall rather than one of Nathan’s airtight suites, are more a distraction than an asset.) The effects and makeup teams have made Ava a robot of strikingly brutal grace, her flesh bluntly disrupted by metallic components.

Fresh off his elegant work on period dramas “The Invisible Woman” and “Testament of Youth,” Hardy brings equivalent visual propriety and composure to a more futuristic mood piece, while composers Ben Salisbury and Portishead frontman Geoff Barrow contribute a bristling electronic score that swarms and simmers with the characters’ own emotional surges. Given Barrow’s presence, one half expects the film to close with his band’s signature hit “Glory Box,” the key refrain of which — “Give me a reason to be a woman” — would aptly sum up its hybrid heroine’s own state of mind.